Follow me:

Sofia

Alexander Nevski Cathedral

a natural bridge between East and West.

Sofia

I have been to Sofia twice, and yet the impressions I carried away were so different that, looking back, it almost feels as if I had visited two distant cities. The Bulgarian capital has this mysterious power: it knows how to surprise, to unsettle, to change its face depending on the gaze and the moment in which one experiences it.

Sofia is a natural bridge between East and West. You can sense it while walking among its architectures, in the open-air markets brimming with voices and colors, in the daily life that blends tradition and modernity. Here, time does not flow in a straight line: it layers upon itself. The city has changed its name six times throughout its long history; its first identity, Serdica, dates back to the second or third millennium BC, when the Thracian Serdi laid the foundations of what is today the third-oldest city in Europe, after Athens and Rome.

Five centuries of Ottoman rule have left deep marks: you can find them in the Banya Bashi Mosque, but also in the smallest details of everyday life, in symbols and objects. At the same time, Sofia is one of the greenest cities in Eastern Europe: its wide gardens offer respite from the urban noise. In the City Garden, in front of the National Theatre, or in the park surrounding Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, the silence of the trees converses with the grandeur of the architecture.

Walking through the streets, one often stumbles upon emblematic contrasts: just a few meters underground lie the remains of the Roman Amphitheatre of Serdica, coexisting with the imposing former headquarters of the Bulgarian Communist Party, which still dominates the city center.

And right in the heart of the city, at the crossroads of Knyaginya and Todor Alexandrov boulevards, rises the statue of Saint Sofia. Where once stood Stalin, now a sensual yet proud female figure gazes down upon the city: an owl perched on her arm, symbol of wisdom, and a laurel crown in her hand, a clear reference to the goddess Athena. This is the new emblem of the capital, born after the fall of communism.

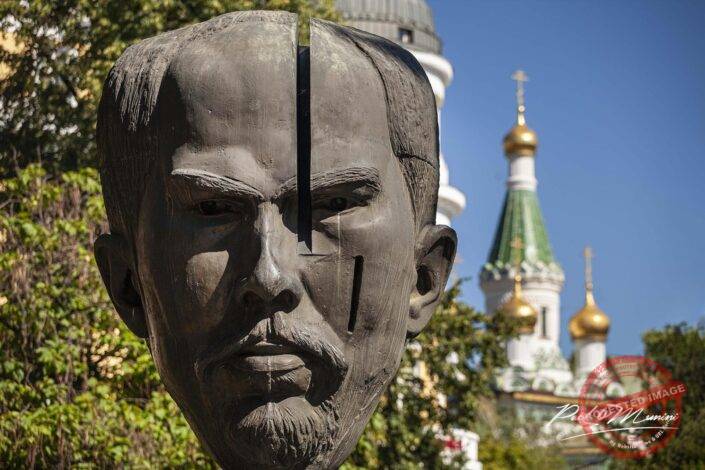

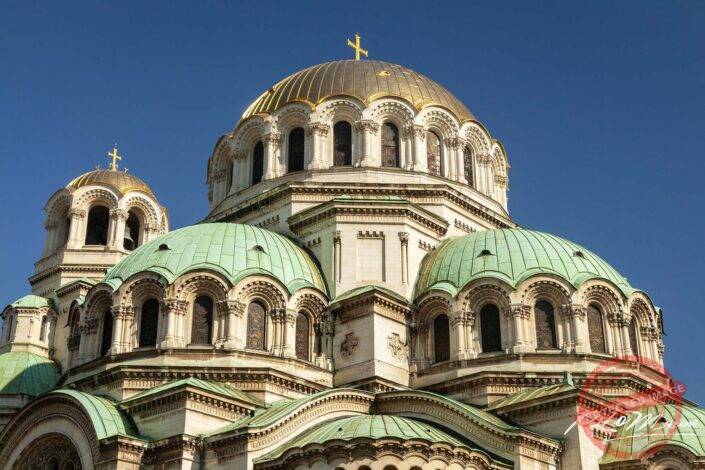

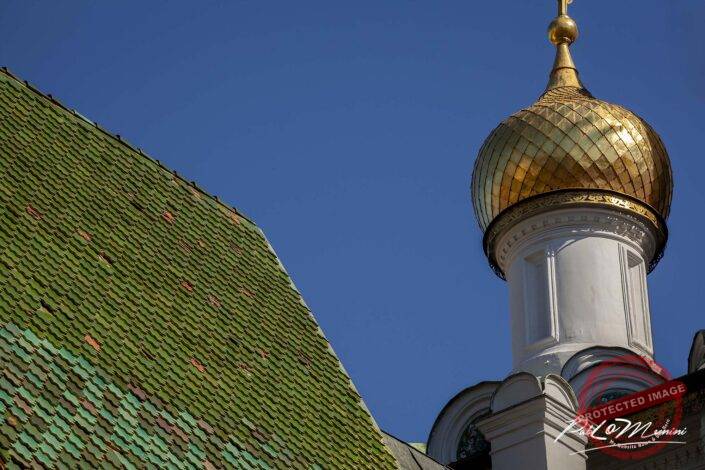

Alexander Nevsky Square is one of the most spectacular places in Sofia. Vast and solemn, it hosts antique markets and open-air exhibitions, but above all, it guards the spiritual heart of the nation: the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral. With its golden domes and neo-Byzantine style, the church is one of the largest in Europe. Built between 1882 and 1912, it commemorates the two hundred thousand Russian soldiers who fell in the Bulgarian War of Independence. Around it, smaller, more intimate churches — such as the 4th-century Rotunda of St. George or the Church of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker — testify to the continuity of faith through the centuries.

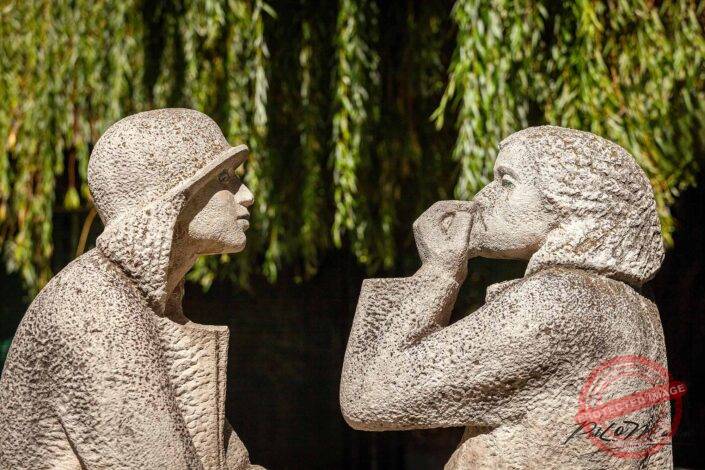

Sofia is a mosaic of memories. In its parks, monuments rise to recall the protagonists of its history: from Stefan Stambolov, one of the fathers of modern Bulgaria, to the statues dedicated to the Opalchenets, the volunteers who fought alongside the Russians against the Ottoman Empire. Every sculpture is a voice telling stories of sacrifice, struggle, and achievement.

This is how Sofia reveals itself: a weave of epochs and cultures, a city that resists being confined to a single image. It unveils itself slowly, among golden domes, wide squares, stone statues, and silent gardens.

And every evening I ended up in the same restaurant in Sofia, because the waiter, in his incomprehensible language, would describe every dish to me in painstaking detail — though I understood none of it. And all night long, the voice of Julio Iglesias echoed through the room, singing in yet another language, equally foreign to the diners. In those moments, I felt immersed in another world, far from my own.

Pablo Munini © Milano, 2025